Driving from Vientiane to Vang Vieng and visiting the caves there. Travel writing.

“Sit in front.”

I oblige with a slight murmur of a protest. There is no arguing with my promised father in-law.

Coco smirks and grins at me playfully, hopping in the backseat like a child.

The SUV crosses town briskly, the roundabouts are left in the dust behind us. Traffic here in Vientiane, the Laotian capital, remains manageable, compared to many cities in Asia.

We soon find ourselves on the main highway, which runs all the way up to Vang Vieng. It’s a brown, two-lane road. Patches of it haven’t been fully tarred yet.

“Six months ago there was no road.”

Young shepherds lead herds of cows and buffalo by the stick, we’re quickly in the countryside, driving through low-lying plains and fields.

Stop by at a gas station. I’m amazed to recognize the brand Super U, a European retail and distribution conglomerate.

Across the street loom the spherical oil reservoirs owned by Total & Co.

The symbolic administrations of the colonial powers may have left half a century ago, but the claws of their corporate griffins remain firmly rooted in the country’s flesh and bone.

Cross a small town with nice-looking houses: red, purple, and bright green, the polished, colorful façades of neo-southeast Asian buildings.

“This is a Hmong town,” informs my father-in-law.

“They’re from over the mountains. Merchant people. They’re very successful.”

The Hmong town disappears. Tractors trudging bails of hay, trailer trucks with loads of people crouched in their rear, students bicycling through the countryside on their way to school, carrying umbrellas to shield their skin from the harshness of the sun, mopeds puttering, slow and fast, hoisting cart loads of produce to the next town; driving through the country is no piece of cake.

The SUV’s hydraulics are hard at work on the unevenly paved highway. Sometimes the tar gives way to an unfinished patch of red dirt, and a cloud of dust forms in our wake.

—

I skip backwards in my account.

The other day, when we had recently arrived in Laos, my father in-law took me to a local joint, hole in the wall. Sat down on a wobbly plastic table, as he ordered two plates of cold garlic chicken on top of white rice. In less than a minute the woman (most shops here seem to be tended by women) brought two steaming plates.

“Good, right?”

“Sure is.”

We wolf the cold chicken and rice avidly, talking little, but brought together by the intangible powers of meal-sharing.

That’s bonding, right there.

After visiting Luang Prabang, we returned to Vientiane. Coco gets to spend time with her parents and family. I stay mostly indoors, living slowly, writing and resting.

I have a jolly time when, one morning, Coco brings a plastic bag full of green leaves and roots to make wraps: “Breakfast.” I end up eating all of it.

It may seem strange that I don’t take further advantage of the opportunities to visit Vientiane and learn more about Laos. Part of this is due to the knowledge that I’ll likely return in the years to come. I do ask many questions about Coco’s family and local customs, taking notes for future use.

Mekong River Dry Construction

Walk along the Mekong River. The hotel and service industry is booming. Many expats come here for the cheap living. Or for women. Or a combination both.

Backpackers usually don’t stay in the capital for long, instead opting to discover the raucous partying scene of Vang Vieng, the spiritual splendor of Luang Prabang, or the lingering history of Pakse.

The country has yet to become a mainstream destination for more upscale tourists, of whom the first few mavericks have appeared. A matter of mere years before the regular onslaught.

I stick to a routine of eating Banh Cuanh or a bag of vegetables in the morning, some writing, resting.

One day we go to the nearby Chinese temple on the banks of the Mekong. It’s been recently renovated but has retained its traditional build. Venerable yet unassuming. I follow the example set by Coco and her father, and wave the wands of incense and kneel for a short devout thought.

“Six months ago they had a break-in. The thieves took the donation chest,” he says, saddened. “That would have been unthinkable, before.”

—

Vang Vieng is nowadays well-known for tubing. What is tubing you ask?

Hundreds of drunk frat boys and girls and all kinds of free-spirited youngsters – tourists and locals lured by the scent of cash – spinning down the river on big rubber lifesavers, bucket-sized cocktail in hand, an activity very briefly interrupted by local authorities for a while after a series of fatal drunken accidents, but whose lucrative interests have fast caused it to re-spawn into action.

Otherwise, Vang Vieng has been traditionally known for the beauty of its sprawling rice fields and swelling river, surrounded by an arena of misty mountains and mile-deep caves, which do better than pale in comparison to the likes of Yangshuo. The literary, romantic backdrop of the traditional Orient has fueled the popularity of the small town.

Now a new guesthouse opens every week.

It’s still noon as we head over to the caves. Early by the standards of the local tourists. We’re welcomed by a virgin turquoise ‘lagoon’, a streaming pond.

There’s a hand-painted sign advising people not to smoke weed. And a tall tree with improvised steps nailed into its trunk. I scamper upwards. I take a look at the plunge. It’s higher than I thought.

“Jump,” says my father in-law, casually.

I obey to the injunction like an animal made to jump through a hoop. The turquoise water splashes about, cold and rejuvenating. When I emerge, he isn’t even looking. Coco’s rolling on the floor laughing.

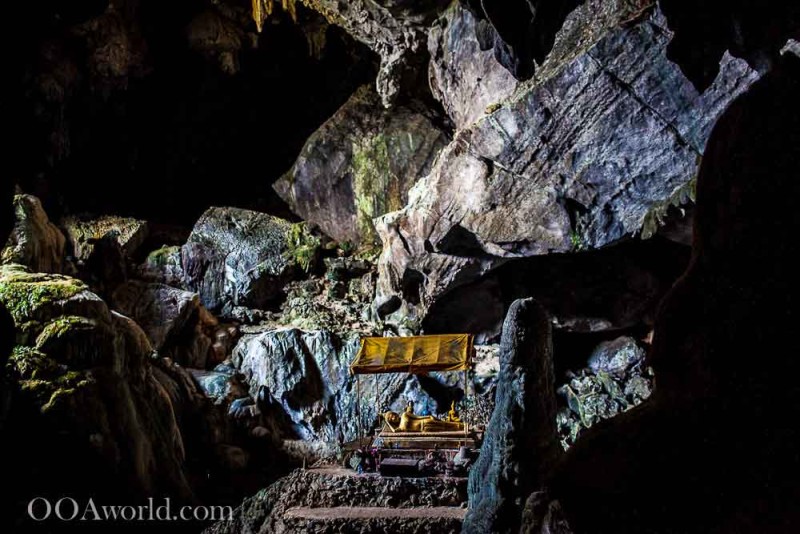

We both tread up the path to the caves. They’re deep and magnanimous. A beam of natural light shines onto a golden lying Buddha, in the middle of the cavity. Its importance is emphasized by the emptiness that surrounds it.

I guide Coco towards the back of the cave. The rocks are slippery and it gets to be very dark. We soon return.

A family is bobbing its head down in unison, silently, in front of the golden statue.

Photos from Vang Vieng Caves and People

“You want to drive? Take the wheel.”

I refuse apologetically. I’m tempted to try, but am too scared of the consequences of mishandling local traffic in front of my father in-law – while using his car. Truth is, I think he may be relieved too.

The roads are lined with bags of cement, sewage tubes and other heavy-duty construction paraphernalia. The country is on the brink of a development boom.

“Vietnamese and Chinese are destroying everything, we don’t even know how many of them there are.” He points to the make of the truck ahead of us. A Chinese brand.

“Vietnam is alright. But the Chinese, don’t give them anything.” Chinese business is everywhere here. Their brands are gradually replacing the Japanese automobile makers throughout the country.

—

“The best sandwich in town. No, in the country.”

It’s nice, for a change, to have local contacts, who can help us communicate with people, taste specialties and discover hidden local gems, as well as hear the points of view of the local population.

Another day, he takes us to have Pho. “It’s the best one around. Some people say it’s because they lace it with special herbs.” He raises his eyebrows.

Coco and I roll eyes, dubious yet curious. The pho melts in my mouth, it’s one of the best I’ve ever tasted. This makes me the more curious to taste it in its original iteration: Vietnamese Pho.

That’s where we’re headed next. I don’t know much about the country, save for Forrest Gump, Apocalypse Now and a few history lessons. As usual, we‘re in the dark. And loving it.

Apparently there’s a beautiful bay surrounded by karst mountains that awaits.

—

It’s not going to be easy to be back on the road. On our own. Part of me is relieved though. One might even say excited. Till now, three months into our travels, we’ve always had some sort of an anchor – the knowledge that we were due to meet with Coco’s family in a month or two. So our adventures have been split into ‘bite-sized’ month-long voyages.

And from my own experience, I know that traveling for longer periods at a time, whether three months, six months, or even longer, is an entirely different experience.

It’s the difference between traveling and embarking on a journey. Between going from one place to the next, and letting the places seep through you.

It’s the difference between moving without, and changing within.

So I’m relinquishing the opportunity to change within. To feel ‘that’ feeling. To live up to the incredible chance that we have, and not let it slip through too quickly.

Fortunately though, by now it’s becoming crystal clear that our travels will not be confined to the vague six months we had originally carved out – not if we plan to make it all the way to India anyway. And we’ve been getting much better at budgeting our stay, and watching out for each and every cost.

There remains one anchor…

I’ve been in touch with my former employers, who’re organizing a conference in Bangkok next month. I figure this might be a good way to re-kindle some old contacts, and promote the projects I’ve undertaken. I’m not entirely free yet.

I plan to show up at the conference. I’ll need some shoes and a suit.

This reminds me of the early days of ooAmerica, driving long-haired across the United States, only to interrupt the road trip while in the middle of the Texan desert, in order to fly back mid-trip to assist with a business development venture in Europe. Before flying back and sleeping sweat-fully in Fanta, my dear minivan, in the hundred-twenty degree Texan summer. Good times.

—

Thank you Laos. I hope to see you soon, safe and sound.

Next: Video interviews from Laos and a video time-lapse of the monks alms giving in Vientiane. Then Vietnam.

For more stories, photos and videos from Vang Vieng and Laos, have a look at the Laos section.

If you plan to visit Vang Vieng and Laos, check out Rolling Coconut’s Vang Vieng travel tips and Laos itinerary.