Kaiping fortresses, Diaolou

The night bus from Yangshuo comes to a stop at 2 or 3am. Coco and I lay fast asleep, unaware. We’ll realize a few hours later that we had arrived at our final destination, Guangzhou. People are allowed to remain aboard the bus till dawn, a courtesy much appreciated – and which we’ll never enjoy again during the remainder of the trip.

A cab circles the interminable city ring before dropping us off at the foot of Coco’s aunt’s high-rise, where we crash a few extra hours.

Today’s Sunday: we have some seafood with the family, stroll, rest.

The next day, we’re up and going. Our Chinese Visa expires tomorrow. A Google Image search alerts us to a peculiar landmark in the region: the Kaiping Diaolou, or fortresses, are a vast ensemble of incongruous rural mansions built as early as the 16th, all the way through mid-20th century, by successful Chinese emigrants upon return to their homeland.

Influenced by the sights and monuments gleamed during their travels around the world, the successful laborers and merchants ordered the construction of castle-like mansions to serve the dual, and somewhat paradoxical, purpose of boasting of a family’s wealth while protecting it from the envy of bandits. The result is an architecturally eclectic mix of Byzantine, Western and Oriental features: square-based towers rising more than a hundred feet in the air, surmounted by Roman domes and cupolas, overlooking bright green rice paddies…

I’m sold.

Village near Kaiping

We lack any game plan whatsoever, but with more than 1,800 of these fortresses still standing in the Kaiping area alone, we figure we’re bound to run in at least a couple. This is our first mistake in a series that will precipitate us into an unworldly, zombie-like, wasteland.

So we head over to Guangzhou’s bus station, and book a ticket for the provincial town nearly a hundred miles away.

I watch the scrolling panorama of flooded paddies, reservoirs, and low-lying plains, reminiscing upon the sights and landscapes we’ve visited during our month-long stay in China. Already I know I will, and must, return.

After a two-hour bus ride, and past another town whose commerce is entirely devoted to bathroom ware (pipes, ceramics, hooks, showerheads, etc.), we’re ushered into the unpretentious streets of Kaiping.

It takes little time to realize that Kaiping is now only the shadow of its glorious past, one during which the region’s emissaries populated the five seas and four corners of the world, only to later return home to a melting pot of cultural and economic success.

We make way towards the only, large, and emptier, restaurant, where we’re charged both for the tea kettle which was already set on the table (though we didn’t drink from it), and for ‘renting’ chopsticks.

It’s past noon and time to face our unpreparedness. Coco, for all her good will and skills in foreign languages, has a hard time expressing the idea of ‘fortresses’. We end up climbing into a local bus, grinning at each other as we tumble along the road, unsure what to expect, past decrepit shops and chicken cackling in cages.

As we exit the city, a decrepit building briefly catches our attention – could it be one of the fortresses? The bus clamors onto the country road, through marshes and rice paddies, past one industrial complex after the other.

Suddenly, the bus comes to a stop and the driver fervently motions at us. We’re kicked off the bus, wondering if he ever understood our intentions.

A farmer near Kaiping

A worn sign reassures us: the nearby village is home to the region’s oldest standing Diaolou.

“Well, here we are.”

The air is thick with pesticides and toxic fumes from the nearby waste treatment plants – or at least I assume that’s their function considering the violent outpour of acrid smoke erupting from their chimneys, hovering above the fields and, eventually, into them.

We follow a path towards the village; a farmer drives a rice tractor in circles among the greenish paddies. There’s neither smile, nor any recognition whatsoever, as I snap a few pictures. A venerable tree overlooks the village square, populated by a dozen old ladies ensnared in wool shawls. They eye us conspicuously as we walk by, with neither interest nor disdain, their movements solely animated by the overwhelming morosity of the place.

The water basins, which provide irrigation to the fields as well as drinking water, lie stagnant, pools of chemical green overwrought with algae and marine weeds. The silence is eerie, only altered by the distant hum of the tractor and the plant’s incineration chambers.

We ask for directions to some of the old ladies. They all share strangely crooked faces, smiles that reveal gapping teeth, a sun-beaten complexion that burrows deep wrinkles into their features.

Their answer is muttered grimly, swept by the green wind and deafening silence.

Old ladies near the Kaiping Diaolou

“This place is weird,” I whisper to Coco as we continue into a narrow alley.

I peek into the doorless houses, dark and bare-floored. An occasional animal destined for future consumption fetters in his cage, the alley’s walls hover closer to us.

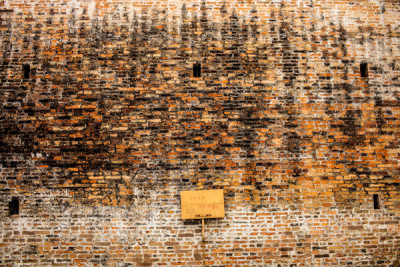

We’re relieved to stumble upon the diaolou after just a few paces. The alley leads to another square, where two or three bored vendors tirelessly peel cloves of garlic, setting them at their feet with the others. The ‘fortress’ itself is an altogether unimpressive red-brick granary. We’re gratified with a plaque which reads “Oldest extant diaolou, built during the Ming Dynasty, 1522-1566”. That’s it really.

Venture down another alley, followed by the echoing sound of our footsteps, the distant bark of a stray dog. The skies are heavily clouded over, motionless, distilling sparingly the dull rays of the sun. Only the smoke trails from the nearby chemical plants ceaselessly waft through the swollen skies, saturating the landfill air. We’re caught between the vapors of pesticides rising from the whitewashed water of the rice paddies and the downwind downpour of toxic fumes seething from the skies.

I begin to wonder if this precarious living situation may have an impact on the behaviors and physiological attributes of the local villagers – Chinese Erin Brockovitch, this is your call!

A woman squats by a gloomily green basin, washing her dishes. She doesn’t even seem to notice us, as she repeats the motion of dipping the plate into the marsh, scrubbing it, and setting it aside.

I feel like we’re walking through a wasteland populated by lifeless phantoms. The thickness of the air is also blurring my senses.

“Can’t wait to taste her dishes.”

We’re trying to fight the implacable grimness of the skies with ‘tasteless’ humor.

As we turn another corner, amongst patches of dying grass and decaying litter, a dog barks us away. We return through another set of alleys, which brings up little but more trash, nothingness and death.

The old ladies sit on the village square, below the venerable tree. I peek into a house on the village square, where the men drink away their days to the rhythm of pool and card games. Coco attempts to muster an interview from the old ladies. Their wrinkled faces and bulging eyes shoo us away.

They laugh amongst each other as we leave, increasingly disheartened. I can’t help but think we’re in the scene of a zombie movie.

“Good thing we’re leaving now, I was beginning to feel dizzy from the noxious air.”

A farmer in Kaiping

The afternoon is winding down and it’s become clear we’ve been duped by the bus driver, the postcard promise of Google Images, and, when it comes down to it, our own unpreparedness.

There also remains another problem: there’s no bus stop whatsoever as our driver dropped us off in the middle of the road. As much as I hate to admit this excursion was a failure, and as much as I’d like to venture further into the unknown and get a glimpse of some of the more spectacular diaolou, the obstacles far outweigh the time at our disposal: assuming we can catch a local bus onwwards, we still have no idea where to go, and risk a similarly disappointing experience even further away from Kaiping, only to miss the last returning bus to Guangzhou.

Coco’s less than enthused by the overall development of the plan, and I feel responsible: it was my idea to come to Kaiping, and part of our unpreparedness (for example not knowing the name of a specific village or fortress) was deliberate. I’m trying to get us to feel comfortable in these unknown situations, to acquire the reflexes needed in order to travel more unpredictably while staying safe.

It’s still early in the trip and I want her – and us – to be prepared in the future for the many good or bad surprises that abound on the long journey we’ve undertaken. We’ll be in the Philippines and Manila within a few days, which will be an entirely new ball game. Still, it’s a tricky task converting a risk-adverse person, and can only be done in implements. That we’ve left in the first place and made it till here is already such a huge step!

“Don’t worry, I’m sure we’ll find a bus or a way to get back. There are a few houses across the road, maybe someone can help us or give us a ride.”

We agree to soon return to Kaiping after exploring the surrounding area, should we be lucky enough to find another far more impressive fortress tucked behind the fields across the road.

Clouds of insufferable dust follow us as we cross, and I stare at the chimneys of the plant, puffs of smoke tumbling out assuredly above the grey and green rice fields.

We walk on a path into the fields, past another industrial building, possibly a paper treatment plant, or simply a warehouse for the plant on the other side. The air doesn’t taste as acidic here, although the paddies are illuminated in the same dull light of the clouded skies.

A man with a fishing pole squats by a flooded rice paddy. He responds to our presence with marked unawareness.

There’s no diaolou in sight. It’s almost time to admit defeat.

A crowd of peasants are busy at work in the fields. A dozen women, lined each in their furrow, pace forth at the same rhythm, busy sewing seeds. We hear them heartily sing from afar, a welcome respite to the eerie silence of the place.

One woman stands on the path, shielded by her coolie hat, eagerly taking gulps from a water bottle. We ask her a few questions, with little understanding of her answers. But she has a good laugh anyhow, and so do her companions in the fields.

The clouds above are at last moving, and the sun’s rays timidly appear on the rice paddies and the faces of the women at work. We leave the rice bearers after a few laughs, smiles, and waves, relieved by the lightened atmosphere.

A rice bearer in Kaiping takes a drink

Returning to the main road, we must face our last problem: catching a bus back to Kaiping, if there’s any. There’s no person in sight, only the low hum of the waste treatment plant and the whistle of the wind pervaded with pesticides and dust. After a while, an old man joins us. After more ineffective communication, we gather he must also be returning to Kaiping. So we wait.

A bus does in fact eventually show up. We hop in gratefully, leaving the desolate wastelands with no remorse.

It’s fair to say this excursion was a ‘failure’ – one of first of the trip – at least in terms of time spent for the little we saw. I look at Coco affectionately and apologize for bringing her here.

She looks at me lovingly, also relieved: “We’re okay, thanks to you.” I hold her warm body closer to me, because this wasn’t a total failure after all.

In retrospect, I guess this would have been one of the rare occasions when dishing out the extra price to hire a driver would have been a more effective use of our time despite our backpacker budget – not that we’d be willing to reiterate a special trip from Guangzhou for the fortresses alone, at least judging by the little we saw.

In the end, we also got to see another facet of the reality of modern-day China: the promiscuity of frugal rural life set against the backdrop of unfettered industrial development. And so happened our last day in China.

- Village near Kaiping

- Old ladies near the Kaiping Diaolou

- Shop in Kaiping

- Kaiping fortresses, Diaolou

- A farmer near Kaiping

- vendors near the diaolou

- A rice bearer in Kaiping takes a drink

- A farmer in Kaiping

Find out more about travel tips to Kaiping Fortresses on Rollingcoconut.com!

fantastic piece. The photos are lovely, and so is the narrative style. It reads like a page from a travel novel. I especially like the last line of this blogpost.

Thank you, and sorry for the delayed response. Will do my best to keep it up!

It’s good sometimes, to see the life lived by the people behind the tourist courtain. As always, great shots and writing.

Fully agree, will keep seeking to peek behind the tourist curtain. Thanks!